BANAM

One of the ancient musical instruments of the Santals

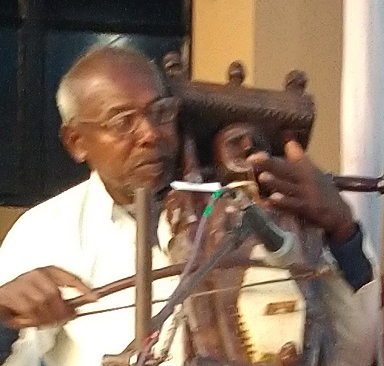

Banam, a single-string wooden lute or fiddle, is one of the ancient musical instruments of the Santal tribe. The instrument is made of wood; the lower part is covered with Bengal monitor lizard-hide and tightened with bamboo pegs. According to its different shape & size and types, the Banam has different names and creates various tunes. Banam-Making is an art, and not many people among the Santals are still engaged in it.

There are various stories on the origin of the Banam which are mostly related to Bongas (spirits). One such – highly symbolic – story about the Banam runs like this: A long time ago, there lived a family with five brothers and one sister. The brothers used to hunt in the forest for a living, and the sister grew vegetables and collected firewood. One day when the sister was cutting vegetables, she hurt her finger and a drop of blood fell on the vegetables. Her elder brother saw this. On that day, the vegetable curry tasted very good. The elder brother told his other siblings about the incident and they wondered if her one drop of blood had made the curry so delicious. If so, how much more delicious her flesh would be! So one day the brothers killed their sister and cooked her flesh. Everybody got their share of flesh and ate it, except the youngest one. He was very fond of his sister and he became very sad about the killing of her and the incident which followed. So he buried his share of flesh in the backyard of their house. Over the years, a Guloj tree with many flowers grew up in the place where the flesh had been buried.

One day, while walking past the tree a “Koimar Jugi” (member of a clan who walk around the villages begging and singing) got attracted to the tree. He cut it and made a Banam from it and begged while playing the Banam. One day the Jugi got to know the five brothers who were married by then and lived separately. As the Jugi played the Banam, the brothers were shocked and puzzled at its melody. The sound resembled their sister’s plaintive voice. They bought the Banam from the Jugi, but none of the brothers could keep the Banam with him at night because from the Banam emanated the sound of their sister’s cry. But when the Banam handed over to the youngest brother, it stayed calm, and since then the Banam stayed with him. This is believed to be the first Banam of the Santals. This story must be understood on a highly symbolic level. The eating of human flesh here is symbolic of how deeply the musical instrument ‘becomes’ the essence, the soul of the human being who ‘possesses’ the Banam –or who is ‘possessed’ by the Banam.

Traditionally, the Banams have human faces, faces or masks of animals, birds and sometimes of the abstract figures of Bongas which are carved on them. Nowadays, figures of contemporary stories are also being depicted. Banams mostly accompany the songs that are related to the spirits and ancestors, like the songs in the Dqsqe Parab (Dasai Festival) or the Bhandan (Death Rites). Thus the Banam is not only a musical instrument that makes music and gives joy, but it also has a great role in creating the ambience to connect human souls with their ancestors and spirits. The songs that go with it the Banam help us to understand the deeper meaning of the spiritual and religious life of the Santal community.

Organized by Bishnubati Adibasi Marshal Sangha . Supported by Ghosaldanga Bishnubati Adibasi Trust. Financial support Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo, Norway. Photography by Samiran Nandy and Boro Baski

BANAM MAKING WORKSHOP

Banam plays an important role in the Santal cultural heritage. However, the making and use of the Banam is declining among Santals and is threatened by extinction. The old villagers who have imbibed our traditional knowledge and normally make and play the Banams are unable to transmit their skills and knowledge to the young generations. The young mostly remain busy preparing school lessons and therefore get little time to sit with the elderly people of their village and learn from them. Another reason is the young generations’ attraction to the fast and loud music from Bollywood and from other modern sources.

Against this background, the Ghosaldanga Bishnubati Adibasi Trust organized a Workshop on Banam Making in the campus of the Museum of Santal Culture at Bishnubati. Traditional Banam makers and the young generation of Santals who have an inclination towards Banam making have been invited to make the Banams during a three-month workshop (September to November 2018). In the last phase of the workshop the Banam makers have given final touches to their instruments, like covering them with cow hide and reptile skin and arranging the tunes been done in their respective homes. The main objective of the Banam workshop was to preserve and to transmit the traditional art and the knowledge of Banam making and to create awareness about the importance of this art that incorporates such rich stories and histories about our lives. We illustrate this booklet with pictures of the Banams that have been produced during the workshop. Further, the Banam makers have shared their personal journeys with their own Banams.

Saheb Ram Tudu

had a strong inclination of working with wood, bamboo, mud and other natural materials from early childhood. I grew up with my father. Seeing him make all the household materials himself probably influenced my interest. Starting from the cot to the bullock cart, from the thatched roof to multiple musical instruments and hunting materials, my father never hired craftsmen to manufacture such works. Without compromising with my studies, I emulated my father’s interests. I studied sculpture at Banaras Hindu University and animation from the National Institute of Design, Allahabad. Presently, though I stay in Kolkata for a job, my interest in working on traditional items remains alive in my heart.

I had heard many stories about the Banam in my childhood including the one about the creation of the Banam. I remember my uncle and aunt quarrelling because of playing Banam in the evening. My aunt believed that the Banam my uncle played had a spirit dwelling in it; she heard the Banam playing by itself at night. To satisfy the wishes of my aunt, my uncle used to keep the Banam hanging in the backyard of their house at night.

In my Banam I consider it a lady or flower, and I have depicted over it the Guloj tree. The myth says that it is the plant that grew on the burial site of the sister who the five brothers killed to eat her flesh. The figure of the elephant depicts the supreme power that emerges from the mystery of divine emptiness inside the “belly” of the Banam which is covered by goat skin. I feel that it is from the divine emptiness that the strength of Santal culture and the beauty of life and music evolve.

Som Murmu

I grew up seeing my father making bullock carts, ploughs and bamboo cots under the tree in the backyard of our house. He also used to make roof ridges of wood or bamboo and cover them with tin and bamboo for other villagers in exchange of rice-wine, food grain and sometimes money. After my father’s death I took up his job besides the agricultural work. And that is how I was introduced to wood work and making of musical instruments like the Banam and flutes.

I took up Banam making seriously when I met the legendary Banam maker and player Bajjar Hembrom of our neighboring village, Pathalghata. For many years we have been experimenting with Banams and other Santal musical instruments and songs in our villages. A few years ago Kristi, an NGO working on promoting tribal art and culture took my Banams and other manual work like chader badani, wooden dolls, materials with bamboo and grass to sell them in the fairs like Poushmela, Maghmela, Khoyai Hat and other fairs in and around Santiniketan. It is the first time that I came to know that the Banam has a monetary value and non-Santals also buy them. Now I make Banam only on request but I play it regularly during our festivals – in Dqsqe, Sorhae, Baha and during our marriage festivals. Playing Banams while having rice-wine in our courtyard in the evening gives me physical relaxation and sense of joy and belonging with our community.

The sculpture that I have depicted on my Banam tells about the struggle and joy of an old widow. She takes care of her two children and is also responsible for her grand-children whose parents have separated. Their father has gone far away with another woman to work in a rice mill.